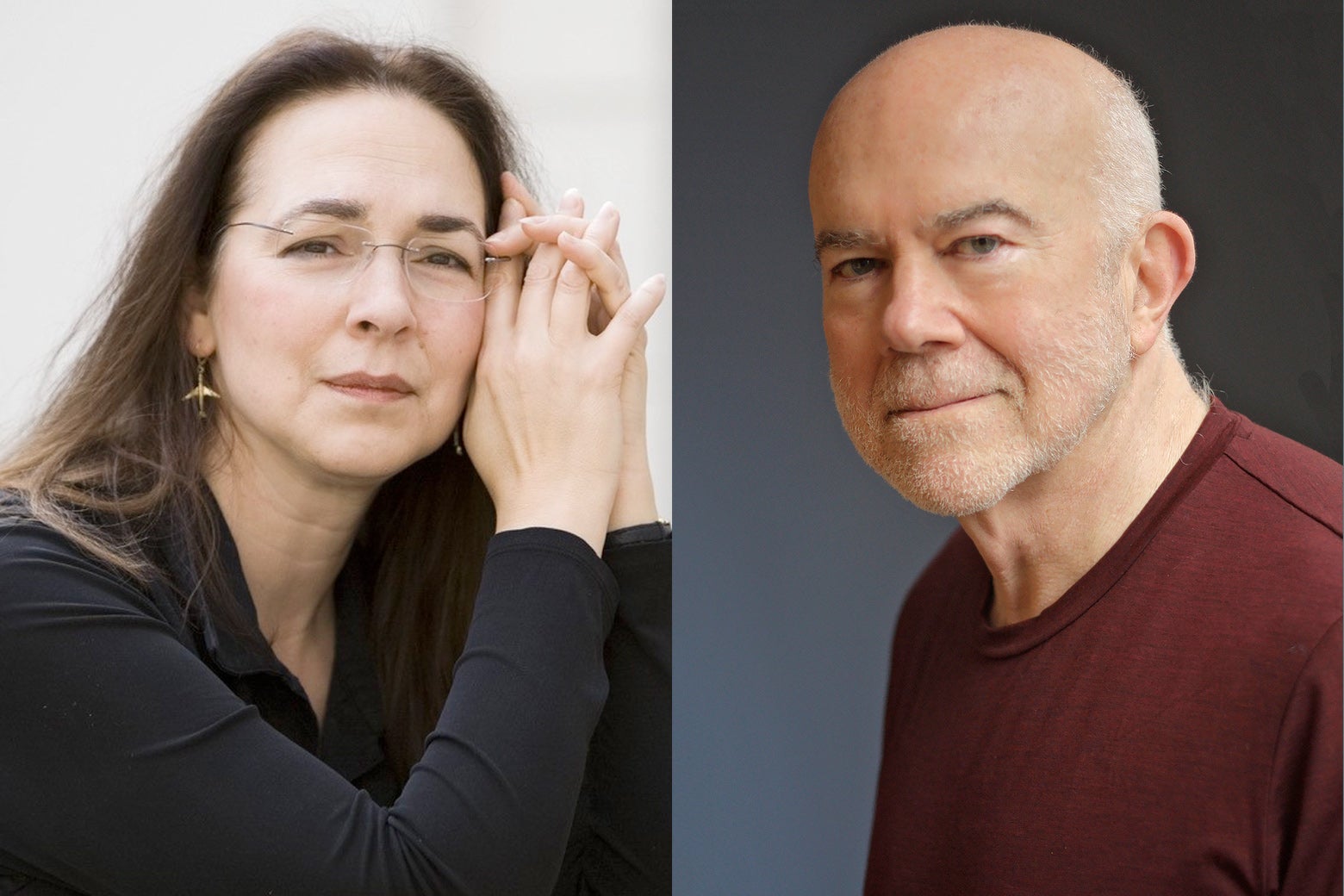

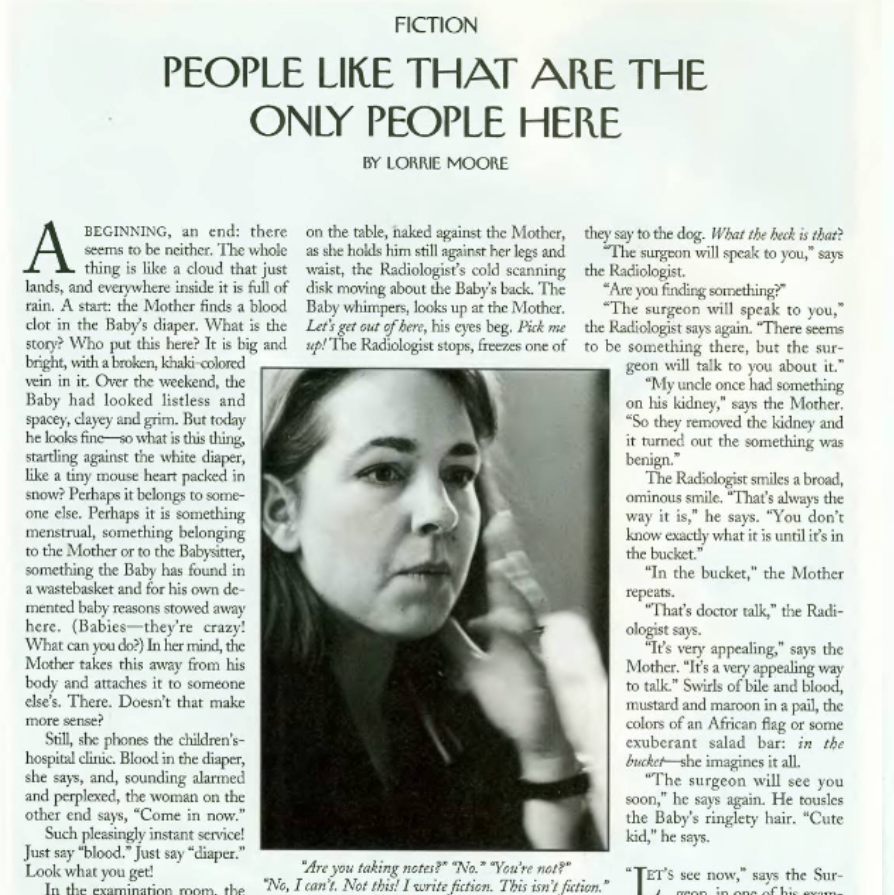

In a profile of the author Lorrie Moore published this week in the New York Times Magazine, I wrote about the memorable 1997 publication of Moore’s masterpiece, “People Like That Are the Only People Here,” in the New Yorker. The story, about a mother whose baby has cancer, brought enormous attention to Moore and her family—which led to her becoming very protective of her privacy. In our conversations, Moore told me she had always been upset by the magazine’s decision to publish a photo of her alongside the story, as if to connect her own life to the story’s characters. She blamed the New Yorker’s fiction editor at the time for that decision.

That fiction editor was Bill Buford. He’s best known now as the author of the seminal Among the Thugs and the bestselling cooking memoirs Heat and Dirt. But in 1997, he’d been freshly hired by Tina Brown from the London literary magazine Granta to revitalize the New Yorker’s fiction section. While reporting the profile, I called Buford to discuss Moore’s experience. The resulting conversation was a fascinating exploration of a transformative era in magazine publishing, an intriguing glimpse inside New Yorker culture, and a thoughtful look at the regrets an editor might have, many years later. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Dan Kois: Lorrie and I were talking about the publication of “People Like That Are the Only People Here” in early 1997. We sort of got into an argument about it! She hated that you put that photo of her on it. I said that was clearly the best way to publish a story where so much of the power comes from the play between life and art. What she remembers is that you told her it was for some kind of contributors’ page and she was surprised and unhappy that it appeared with the story as an illustration. She told me you later apologized to her for that. How do you recall that event?

Bill Buford: Well. I’m glad she remembers I apologized, because I certainly should have apologized. I doubt I had a very active hand in it, but I possibly did. I’m thinking about how to say this: The editor at the time was very keen to see fiction be actively competing with the narrative appeals of the rest of the magazine, in a way that called attention to itself, instead of buried in the magazine, like something the magazine “had” to do.

The editor being Tina Brown.

Yes. I had been at Granta, where we published nonfiction and fiction and it was often hard to tell the difference between them. I was fond of fiction that read like nonfiction, and nonfiction that read like fiction. You know, the so-called traditional New Yorker story was exploiting autobiography—it didn’t need to pretend to be autobiographical—but in a lot of ways, it covered the ground that was later covered by the craze in memoir. A lot of that New Yorker fiction was so felt and specific because it was exactly in that area, without ever having to declare it.

I reread the story. It’s pure genius in every sentence. Fantastic sentence-writing. There are similes that etch themselves into your eyes. It’s deliciously subversive, and it is definitely explicitly inviting the reader to blur fiction and nonfiction, without ever revealing to the reader if it is true or not true. It is a work of fiction that’s very cleverly playing with what fiction is. It’s in a lovely spot. That’s how I would imagine Lorrie would view the story, and by publishing a picture of herself in the middle—was it in the middle? Not the facing page?

Yes, the first page of the story has the title at the top, and then three columns of text surrounding the photo inset in the middle.

Ooohh. Yeah, I don’t think that would’ve been at my instigation. Another department would have done that, and it would have been very hard for me to overwrite it. I feel guilty now if I didn’t take a more active hand! I certainly understand her hurt.

I see why the magazine did it, though!

I recall there were these Paul Theroux pieces about meeting the queen and meeting Anthony Burgess. They were fiction, but they were very close to nonfiction, and Paul was very clear about how they were drawn from real life. We published them with a different rubric—we called it “Fact and Fiction.” Well, one of the staff writers was apoplectic about the blurring of the genres and the deliberate obfuscation. And he insisted that we never do it again. That writer was this former sports journalist named David Remnick.

Oh my god!

I think he was completely right! I was chastened. His argument was that fact was fact, and the magazine’s integrity depended on that.

So what role did Tina play in art decisions like this?

You know, there were many times I would go look at the board with Tina and she would look at the magazine not like I did—she would look at the spreads purely visually. To her mind there was a visual vocabulary to the spreads.

I believe in her diaries she describes doing this with issues of Vanity Fair, too.

I came from a magazine that was all about the words. I was so baffled—there were hours spent at the boards looking at what I felt was kind of an imaginary—imagining a reader who’s flipping through the magazine on a subway. But then I would be on the subway, and I would see readers treating the magazine in exactly that way. Flipping to an article, looking at it, skipping it. Flipping to the next, skipping it. And then the next article something grabs them, and they settle in to read.

So it works.

I don’t remember making that decision about Lorrie’s piece, but I do remember what the culture was then. Word people didn’t have much authority when they had to stand up next to visual people. To come up with a picture in a story that feels so autobiographically inspired—it’s meant to trigger a kind of voyeurism. It’s not what an author likes to do, but it’s what a publisher loves to do.

Exactly.

And I can see why she responded that way. The magazine will be very scrupulous about every word, every piece of punctuation. The author would know about every change. The magazine would never change the title of a piece of fiction, for example. But she was off in Wisconsin, I believe, so something like this …

You weren’t sending page proofs. It’s likely Lorrie never saw the page layout until the magazine arrived in her mailbox.

Yes, exactly.

It’s so interesting to hear you expressing regrets now because I argued with Lorrie about this. I told her it seemed to me that the photo was tremendously effective in highlighting those themes. It gave the story this incredible heat.

And you’re a reader! That’s evidence that the publishing decision worked. It worked on you.

It sure did.

I don’t know if Tina remembers, but Tina would love that heat.