After centuries of oftentimes bloody fights against deeply engrained white supremacist views, most Americans of goodwill today recognize that racial bias is wrong. In the early 20th century, the mayor of Baltimore could gain popular support by backing local zoning laws that divided neighborhoods by race on the grounds that Black people should be kept apart—by government fiat—to reduce harm to white people. Today virtually no one would support that type of policy.

But what about class bias? Is it OK to pass exclusionary zoning laws that outlaw multifamily housing and keep poor and working-class people out of towns and local public schools on the basis that they won’t pull their weight in contributing to the community or will likely make undesirable neighbors? In a fascinating article in the Atlantic, Reihan Salam, the president of the conservative Manhattan Institute (and a former Slate columnist), essentially defends that position.

It should be noted that Salam can’t be written off as an unhinged right-winger. He is often a thoughtful commentator, whose 2008 book with Ross Douthat, Grand New Party, argued that Republicans should do more to serve the interests of working-class people. And he personally opposes exclusionary zoning because it reduces economic productivity and artificially increases housing prices. “Among economists and legal scholars who work on local land use, the debate over zoning reform is essentially over,” he notes.

But in a deeply troubling turn, Salam argues that discriminatory attitudes toward those of modest means are so engrained that, as a political matter, it would be a huge mistake for “yes in my backyard” zoning reformers to call out class bias.

Salam defends the right of wealthier families to exclude low-income and working-class families in part because he suggests that hoarding resources is reasonable and maybe even an inevitable feature of human nature. In deciding whether to adopt government laws—such as minimum lot size requirements—a community is perfectly justified in using that tool to ensure that only wealthy families will be part of the community. “While some newcomers will generate more in local revenues than they receive in services, others will not,” Salam explains. It is entirely rational that wealthy people would want to avoid “fiscal intermingling with lower-income neighbors” who have “different needs and priorities.” Indeed, he writes, “given these powerful fiscal incentives, NIMBYism in small suburban jurisdictions is almost inevitable.”

Here we have echoes of Mitt Romney’s famous worldview that we are not all in the same boat as Americans. The country can be divided into “makers” and “takers.” Why allow a child whose parents service your lawns and provide child care to live in your community when the little tyke’s family won’t pull its weight in taxes to cover the costs of education?

Worse, in my view, Salam also thinks it would be a mistake to question stereotyping by affluent residents that poor and working-class people are bad neighbors. He cites polling research from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which finds that many Californians worry that loosening exclusionary zoning policies that keep low-wage and working-class people out could “result in crime, noise, litter, illegal dumping and a general lack of property upkeep.”

Salam offers no actual evidence that low-wage workers are, for example, typically noisier. While it is certainly true that crime is higher in poor neighborhoods than wealthier ones, research suggests that most violent crime is committed by a very small group of individuals. Yet Salam is simply willing to accept sweeping stereotyping and thinks it would be a major miscalculation to question those attitudes in any way because he worries about offending the sensibilities of those living in exclusionary communities.

In an earlier era, the same arguments about crime and litter were made by white people as a justification for keeping Black people out of neighborhoods. Today, however, we recognize that even if someone could cite a study showing that statistically one group engaged in, say, more illegal dumping than other groups, it would be profoundly wrong to paint all members of that group with that broad brush. That robs individuals of their dignity.

Some will respond, correctly, that racial bias is worse than class bias. White supremacy has justified abominable crimes, from slavery to lynching, in a way that class bias has not. There can be no doubt that in the hierarchy of sins, a racist is much worse than a class snob.

But that does not mean class bias is OK, or that it is a victimless crime. Economically discriminatory zoning policies, in particular, have much in common with racially biased policies. The common denominator is a shared belief that some of our fellow Americans are so degraded that it is acceptable to pass laws that keep them and their children separate and apart.

The stereotyping has real victims. Consider KiAra Cornelius, a single mother with a daughter and son. When I interviewed her in 2020 for my new book, Excluded: How Snob Zoning, NIMBYism, and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See, Cornelius was working as a claims analyst for United Healthcare. She had been living in a dangerous neighborhood in Columbus, Ohio, and she would drive her kids to her mother’s home, a few blocks away, to visit because it was unsafe for her to walk with them. She longed to live in a suburban neighborhood because she wanted her kids to get a good education—particularly her son, who was a straight-A student. To exclude Cornelius, even if it were true that people in her economic group are more likely to litter or make noise, is deeply troubling.

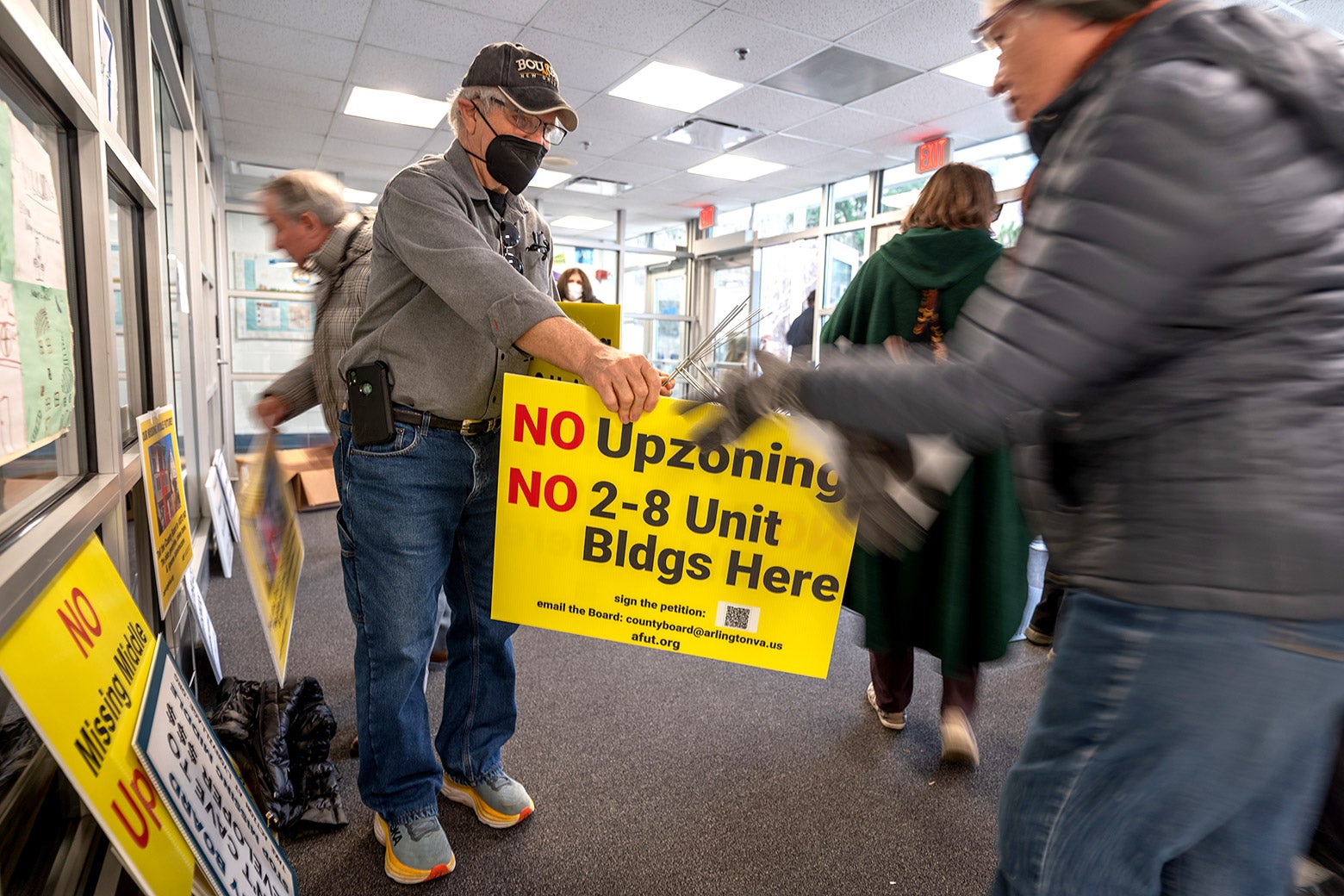

“Treating suburbanites as hateful snobs,” Salam says, will not be persuasive in political battles for zoning reform. True enough, but the point of exposing bias is not to broadly label suburban residents as latter-day Bull Connors. They aren’t. Most are good people who often decided to buy a house where they knew the public schools were strong and don’t give much thought to the zoning requirements of the community. Some (though not all) may be more likely to support loosening zoning restrictions to allow more types of housing if they come to realize that exclusionary zoning imposes real harms and indignities on those kept out. Moral appeals have been part of the political playbook that helped bring about change to zoning in recent years in affluent liberal communities that had been NIMBY strongholds, such as Montgomery County, Maryland, Arlington, Virginia, and Berkeley, California.

Salam says reformers should appeal to the self-interest of suburbanites and to business leaders, and I agree, as far as that goes. Business leaders recognize that it is hard to recruit employees when housing prices go through the roof, and they can and should be important allies in reform to reduce zoning restrictions and increase housing supply.

And efforts should be made to explain to affluent voters—who are generally white voters—how increasing the economic and racial diversity of their communities raises the likelihood of meeting people who will enrich their understanding of the world and lead to a more interesting life than one experiences in a homogenous neighborhood. In more ethnically and racially diverse communities, one is also likely to experience a wider variety of food offerings, live music, and artistic experiences. More pupuserias, Ethiopian groceries, and sushi restaurants. Economically mixed communities may offer a greater assortment of businesses: thrift shops and laundromats alongside higher-end restaurants and shops. And mixed-income communities may also offer a greater diversity of young and old people than do wealthy communities, which tend to exclude younger people.

But why forfeit the complementary moral argument that it can be repugnant to use government laws to exclude those less fortunate? Martin Luther King Jr. and others could have limited their appeal to the idea that advancing civil rights would help America win the Cold War and be more economically efficient because racial bias prevents the most productive workers from being hired. Those self-interested arguments were important, but so was the idealistic principle that a decent society does not denigrate some of its citizens by treating them as if they should be quarantined.

Salam sees the issue mostly through the eyes of advantaged suburban homeowners, so his approach of ignoring class bias also misses out on the chance to activate millions of Americans—of both political parties—who feel disrespected by affluent communities that actively exclude them. Average Americans resent the idea, says George Packer, that under the current system, the deck is stacked so that doctors and lawyers and journalists and professors “go to college with one another, intermarry, gravitate to desirable neighborhoods in large metropolitan areas, and do all they can to pass on their advantages to their children.”

Exclusionary zoning is a key part of the self-perpetuating system Packer describes, and working-class communities of all colors understand it. That’s part of the reason that they have been critical parts of the coalition pushing to change land-use regulations in different states. Salam’s argument assumes that reform cannot occur without the consent of exclusive suburbs, but in places like California and Oregon, populist coalitions prevailed in passing legislation to relax zoning restrictions with the votes of legislators from working-class white rural areas and from working-class urban areas populated by people of color.

It’s not just wrong to ignore and excuse class bias; it’s bad politics too.