The freakishness of serial killers tends to overshadow the people they prey upon. That’s proving true once again since the arrest last week of Rex Heuermann, a 59-year-old Nassau County architect, in the 13-year-old Long Island Serial Killer case. Whether they come across as creeps in their everyday lives or as perfectly normal—alleged murderer Heuermann managed to do both, depending on the social context—serial killers suck all the air out of the room. People who knew or encountered Heuermann on trains, in networking groups, or on Tinder dates have come forward to describe their minor, if troubling, past dealings with him. His neighbors and colleagues and representatives of his family have been interviewed. His tax woes have been discussed on Fox News. His every voicemail message or text or glancing interaction is currently being scrutinized for signs of what Suffolk County Deputy Police Commissioner Anthony Carter described as the “demon” lurking inside him.

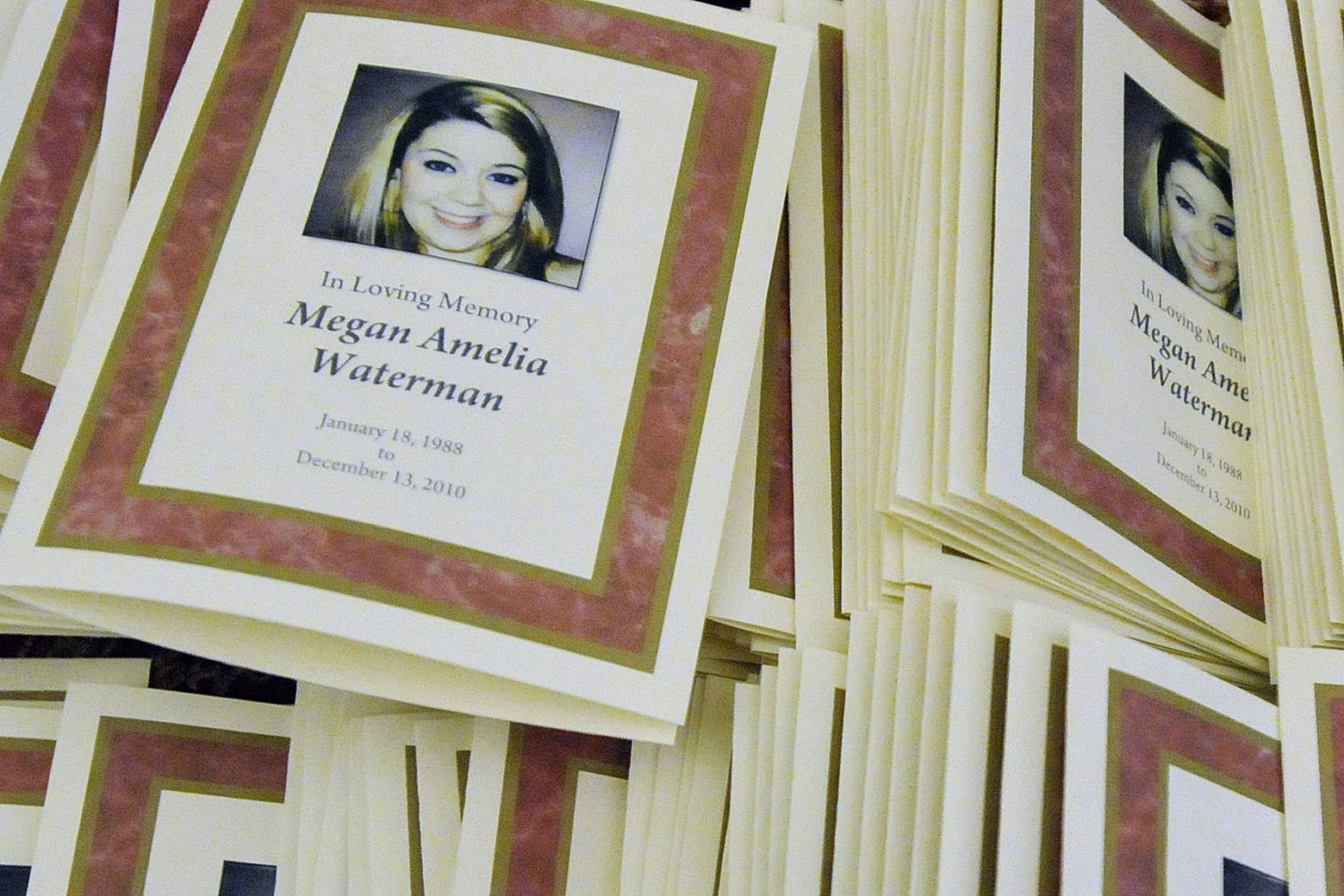

Since 2010—when a police officer training a K-9 search dog along the highway near Long Island’s Gilgo Beach found the body of a woman, later identified as Melissa Barthelemy—the remains of 10 other people have been discovered in the scrubby terrain. But until Heuermann’s arrest Friday brought some relief to some of the families of victims, the case has proved a stubborn mystery. The long delay in solving it has had only one benefit: In the absence of a compelling suspect, the victims known as the Gilgo Four—Barthelemy, Megan Waterman, Amber Lynn Costello, and Maureen Brainard-Barnes—have been given much more attention than serial killers’ victims are typically granted.

Before the public had the demon to fixate on, journalists like Robert Kolker took the opportunity to train the focus on the women Heuermann is alleged to have targeted. In his 2013 true-crime masterpiece Lost Girls, Kolker recounted the lives of five of the identified women whose bodies were found on or near Gilgo Beach. All five lived outside Long Island and worked as escorts, advertising on the internet. Their paths to sex work were varied, scarred by fractured families, mental illness, substance abuse, rape, far-fetched dreams of careers in the entertainment industry, and exploitative boyfriends. Most had intense, troubled relationships with their mothers or the maternal figures in their lives. But one condition unified them: poverty, particularly white, rural poverty, along with the hopelessness it engenders and the perils awaiting those who try to escape it.

The task force whose investigation led to Heuermann’s arrest formed in 2022, over a decade after the bodies were discovered. The evidence the group used to identify and charge him wasn’t newfangled or complex, like the genetic genealogy that helped convict Joseph James DeAngelo, the Golden State Killer, in the best-known cold-case solution in recent years. Instead, an eyewitness had seen Costello, before she disappeared, get into a Chevrolet Avalanche with a hulking man described as having a face like an “ogre.” Because cellphone records suggested that some of the victims vanished in the Massapequa Park area, investigators looked for owners of such vehicles who matched that description. This was enough to get them subpoenas to search Heuermann’s own cellphone records, enabling them to show that his personal phone was never far from the burner phones used to contact the LISK victims, and that most of these calls originated from locations near where Heuermann lived and worked.

This process took all of six weeks, and could have been achieved 10 years ago. A recurrent theme of Lost Girls—and the 2020 Netflix film based on Kolker’s book—is the seeming indifference of Suffolk County police to the crimes. The police chief at the time of the original investigation, James Burke, sent away an FBI team that had been brought in to assist, a decision that baffled observers until it turned out that the Justice Department was investigating Burke himself. In 2016 Burke was sentenced to 46 months in federal prison for beating up a suspect who stole a duffel bag full of sex toys and pornographic material from his SUV. The county’s top prosecutor and one of his aides were also convicted of obstruction of justice for attempting to cover for Burke.

Because Burke himself had a history of hiring sex workers, some amateur sleuths suspected him of being involved in the Gilgo Beach murders, or at least in the disappearance of a fifth woman, Shannan Gilbert, who was found dead in a marshy area 6 miles away. True-crime researchers Billy Jensen and Alexis Linkletter dedicated an entire season of the podcast Unraveled to investigating Burke’s possible involvement in the crimes. Another documentary, 2016’s The Killing Season, speculated that the Long Island Serial Killer had ranged up and down the Eastern Seaboard and beyond, murdering women in Atlantic City and Daytona Beach and perhaps even New Mexico. The investigation of Heuermann has indeed expanded beyond Long Island, but the other locations—areas where Heuermann owned property—are Las Vegas and Chester County, South Carolina.

If Heuermann does turn out to be the Long Island Serial Killer, the theories floated in Unraveled and The Killing Season will be disproved. But both productions helped further illuminate what Kolker showed in Lost Girls: that the crimes went unsolved not because investigators lacked evidence, but because they just didn’t care enough to follow the evidence they had. Burke prioritized concealing his own corruption over fully investigating the case, and his own sleazy extracurricular activities suggest a contempt for women in general and sex workers in particular that led him to regard the victims as inconsequential, throwaway people. The Killing Season documents how widespread such attitudes are in law enforcement. It’s not just the police, however. While covering a press appearance by the victims’ families on the day Gilbert’s remains were found, Kolker overheard a TV crew member remark, “I can’t believe they’re doing all this for a whore.”

As the facts roll out about Heuermann in the coming weeks, this is what he shouldn’t be allowed to overshadow: the women whose lives were taken, and the families, however flawed, who loved them and fought to obtain justice for them. Otherwise, these girls will be lost all over again.