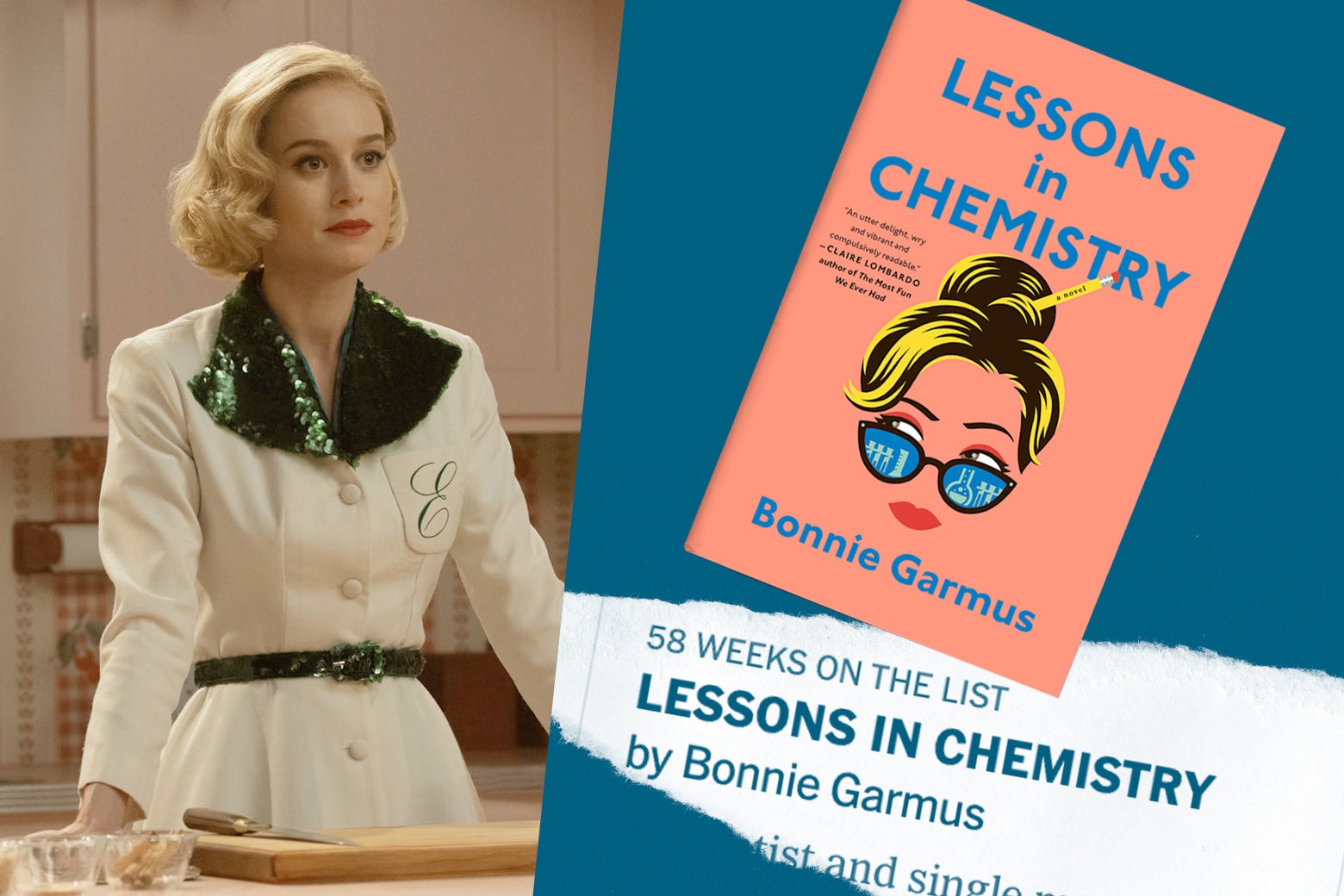

Bonnie Garmus’ debut novel, Lessons in Chemistry, has become one of those books you see everywhere: in the hands of subway passengers and waiting room idlers, on the nightstands of book group members, all over the realm of TikTok known as #BookTok, as Barnes & Noble’s Book of the Year for 2022, and, last but not least, on the New York Times bestseller list for 58 weeks and counting. Last November, the Times noted that it was “on track to be the best-selling debut novel of 2022,” and it seems to have only sold better since. There’s also good reason to believe that it’s only going to get bigger: In October, Apple TV+ will premiere a TV series based on the novel, starring Brie Larson. Garmus, who is 66 and wrote Lessons in Chemistry after a long career as a copywriter, is living every first-time novelist’s dream.

What’s the fuss about? Chances are: not what you think. As the Times article observed, the novel’s American cover is misleading, a cartoon image of a woman side-eyeing coquettishly over a pair of cat-eye glasses against a pink background. Paired with the title, this image shouts “STEMinist romance novel,” a currently booming genre. But Lessons is only incidentally about romantic love. Instead, it’s the story of Elizabeth Zott, a woman chemist and single mother confronting sexism and other tribulations as she tries to pursue her vocation in the early 1960s. She stumbles into a gig hosting a chemistry-centric cooking show on daytime TV and becomes a celebrity in syndication.

Lessons in Chemistry belongs to a genre of literary fiction that could be called the quirky tragicomedy. The novel it’s most often likened to is 2012’s Where’d You Go, Bernadette, by Maria Semple, about a daughter trying to understand her mother’s abandonment. In these books, the main character has amusingly eccentric traits or interests and suffers undeniably serious losses, but the overall tone remains light, with a touch of rueful melancholy and a whole lot of brave soldiering on. After a boom in the 2000s, this style of fiction seems to be increasingly uncommon, which explains why some of today’s readers, raised on plots that milk trauma for all it’s worth, find the novel’s tone confusing.

Elizabeth, who appears to be neurodivergent in some way, gets peeved when a male colleague suggests that she learn to “outsmart” the system, because she can’t see why systems can’t just be “smart in the first place.” She knows that she lives in “a patriarchal society founded on the idea that women were less,” but she indignantly refuses to acknowledge the dictates of that society. After Elizabeth becomes pregnant out of wedlock by one of the few decent men in the novel, and the head of her lab tries to fire her on moral grounds, she seems genuinely astonished, as if she is only just now finding out about the sexual double standard.

Much of the humor in Lessons in Chemistry comes from the collision of Elizabeth’s stubborn scientific rationalism with the unthinkingly conventional attitudes of everyone else. Elizabeth herself has no sense of humor. Her daughter, Madeline, is a similarly brainy prodigy who reads Norman Mailer in kindergarten, shocking her sourpuss teacher, and can’t understand why she gets in trouble for insisting that human beings are animals.

Garmus has an impressive ability to maintain a Campari-like balance of the bitter and the sugary. Elizabeth endures harrowing setbacks, not just a wall of sexism in her career but also a sexual assault and the deaths of loved ones. Trauma abounds in the sympathetic characters’ backstories. Elizabeth’s father, a charismatic religious charlatan, is in prison, and her gold-digger mother is out of the picture, run off to Latin America with her latest rich husband. Madeline’s father, an orphan, grew up in a grim Catholic boys’ school. Elizabeth’s helpful neighbor Harriet has a vile, abusive husband who expects her to tidy up his dirty magazine collection. All of Elizabeth’s bosses (with the exception of the meek producer who makes her a TV star) are insulting, domineering lechers. A more vulnerable woman would be utterly downtrodden by all this, but Elizabeth’s determined single-mindedness and indifference to what other people think of her—the same qualities that tend to alienate her colleagues—provide a kind of shield.

In counterbalance, there are Elizabeth’s improbably studious multitudes of fans, housewives who watch her show, Supper at Six, with notebooks in hand, jotting down her explanation of the hydrogen bond’s role in the cooking process. Elizabeth delivers on-screen pep talks about subsidized child care and encourages one live audience member to follow her dream and apply to medical school, to the cheers of the crowd. There is an absurdly anthropomorphized dog named Six-Thirty (for the time when Elizabeth found him on the street), a noble creature who understands hundreds of words and assists Elizabeth in her home lab. Even readers who don’t care for the rest of the novel—every very popular book inevitably reaps some detractors—adore Six-Thirty.

Call me a cat person, but Six-Thirty seems a calculated bid for reader sympathy designed to shore up the novel’s sentimental side against the harshness of Elizabeth’s life. There are sensitive readers who feel so overwhelmed by the cruelty of Elizabeth’s persecutors—complaints about the lack of trigger warnings are common—that they profess bafflement that anyone could call Lessons in Chemistry a comic novel.

But I’d argue that the novel’s bad guys are the real secrets to its success. Were all men in authority in the early ’60s so comprehensively horrid, a rogues’ gallery of bigots, rapists, plagiarists, and gaslighters? No, but a popular fairy tale—which Lessons in Chemistry most certainly is—needs a thoroughly hateable villain, and this book has several corkers. The dastardly, smug baddies of Garmus’ novel are the engines that drive her plot like a locomotive. You keep reading as much to see them defeated as to see Elizabeth win. To make that happen, Garmus resorts to a final reveal that is pure Dickens—the furthest thing from the collective action that actually made scientific careers possible for women like Elizabeth. Then again, as every Lessons in Chemistry critic ought to bear in mind, too much reality does not a bestseller make.