In April, Richard North Patterson—author of 16 New York Times bestsellers—published an essay in the Wall Street Journal about his difficulties finding a publisher for his first novel in nine years. The book, Trial, tells the story of a Black teenager charged with the murder of a white sheriff’s deputy in rural Georgia, and the efforts of his mother, a prominent voting rights activist, to prove his innocence. According to Patterson, the novel was rejected by “roughly 20 imprints of major New York publishers” thanks to a “new ideology of identity authorship”—“literary apartheid”—dictating that “white authors should not attempt to write from the perspective of nonwhite characters or about societal problems that affect minorities.”

To judge by the many irate comments this essay prompted, and the response to similar controversies in the past, this idea really ticks people off. Skeptics have been known to point out that Dickens didn’t have to be French to write A Tale of Two Cities, and to offer up such reductio ad absurdum scenarios as a world in which only farmers would be allowed to write novels about farmers, etc. Of course, no one is actually arguing that writers should depict only people of their own ethnicity. Most of the controversies over this issue have arisen in a case-by-case manner, with critics making specific claims about individual titles.

The best-known individual title to fall prey to one of these controversies was Jeanine Cummins’ 2020 novel American Dirt. Around the time the book was published to great fanfare, Mexican American critics complained that Cummins had produced a version of the migrant experience that rang false; that Cummins’ publisher, Flatiron Books, had attempted to pass her off as having a stronger personal and ethnic connection to that experience than she actually has; and that the marketing of the book was tasteless. There was a subtler issue of the story’s framing as well. Aspects of Cummins’ novel seem engineered to make the protagonist easy to identify with for the middle-class women who buy most of the hardcover fiction in the U.S.; the main character is a bookstore owner fleeing Mexico City to the States with her small son after a drug cartel retaliates against her journalist husband by massacring the rest of their family. Fast-paced and dramatic, the novel has many of the essential qualities of commercial fiction, but Flatiron got carried away and attempted to position it as, in the words of publisher Bob Miller, “a novel that defined the migrant experience.” Had Flatiron just published it as your basic romantic thriller, American Dirt might have been able to fly to the bestseller lists under the radar of highbrow literary observers. But these grander claims attracted critics who objected to its pretensions to authenticity.

It’s worth pointing out that although media workers consider the American Dirt affair a spectacular blowup, I’ve yet to meet anyone outside the industry who’s even heard about the controversy, and that includes many enthusiastic readers of the novel, which did in fact become a smash hit, selling more than 3 million copies worldwide. Arguably, the number of potential book buyers who care about whether the ethnicity of an author matches the ethnicity of their characters is vanishingly small. Even if Trial stirred up a fuss on Twitter, it’s unlikely anyone in the market for a Richard North Patterson thriller would notice it, let alone find it a reason to pass up the book. But the people who work in book publishing are part of the media, and many, including Patterson, believe that what happened to American Dirt and a handful of other books has publishers spooked.

Since his previous novel, Eden in Winter, was published in 2014, Patterson has concentrated on writing columns and essays on politics and social issues. But even back in his bestselling heyday, his novels were known for their attention to such issues as gun control, the Israel-Palestine conflict, and human rights in Africa. Patterson prides himself on the thoroughness with which he researches these topics, and long before sensitivity readers became de rigueur, he was passing his manuscript for 2013’s Loss of Innocence to such famous feminists as Gloria Steinem and Carol Gilligan, to make sure he’d properly handled such matters as abortion and rape. So what was it exactly that scared the big publishers away from Patterson’s new novel? The author found a smaller publisher happy to bring Trial to press, so it’s now possible to read it and consider this question.

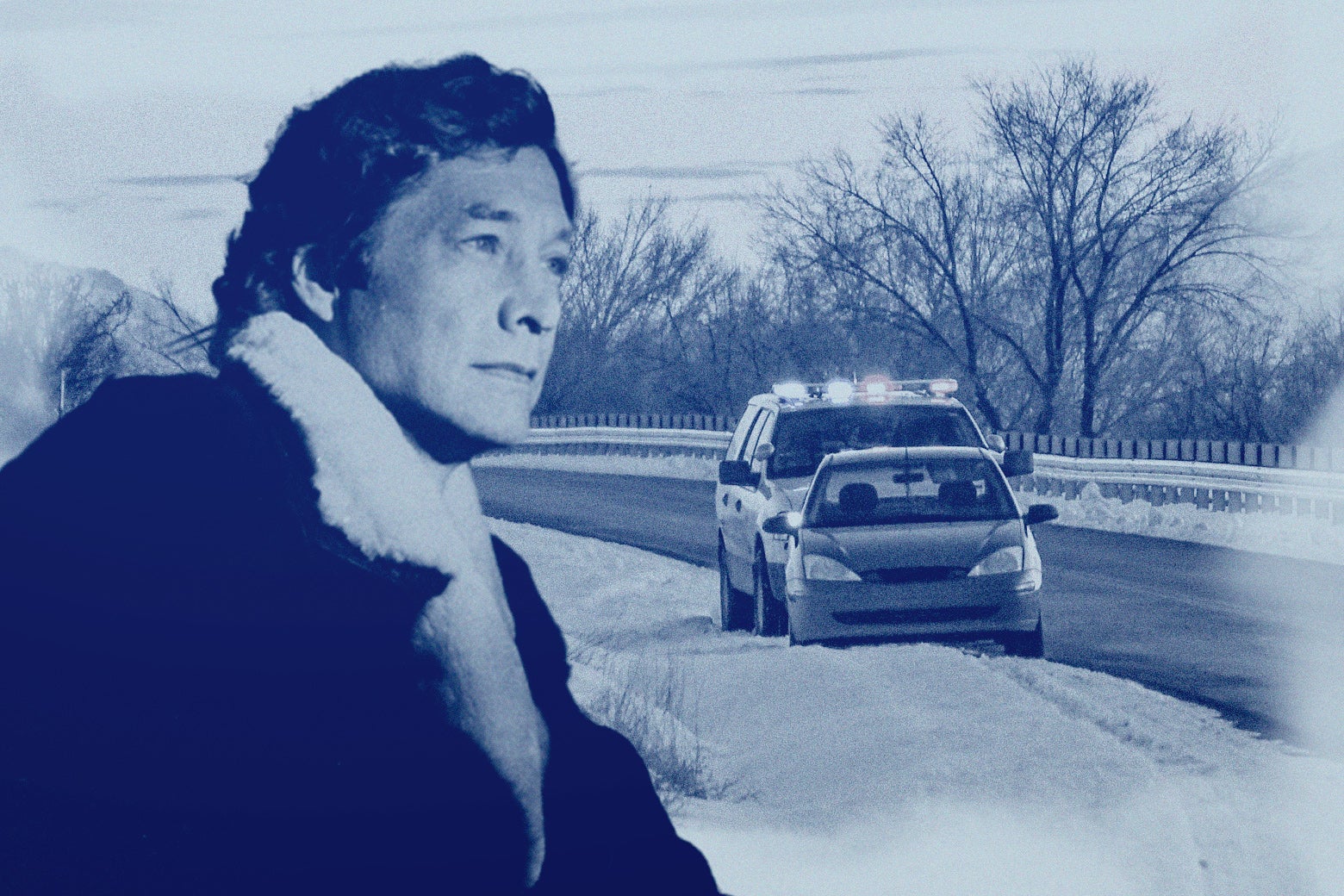

Trial begins with 18-year-old Malcolm Hill being pulled over at night by a leeringly racist deputy who makes it clear he’s about to abuse the kid or worse. Malcolm has been carrying a gun in his car because of the threats he and his mother, Allie, have received for their voter registration work. The two struggle over the gun, the deputy is killed, and Malcolm is arrested. Allie calls her college sweetheart, a Kennedyesque congressman named Chase Bancroft Brevard, to come help. Given that there’s no father in the picture for Malcolm, it’s crystal clear to the reader why she wants Chase involved, despite having walked out on him after graduation while concealing a big secret. Trial slowly builds to the event in its title, a process interrupted by a long flashback to Chase and Allie’s Harvard years.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

This novel is just as intensively researched as Patterson’s previous books, and, boy, do you see that research on every page. Patterson, by his own account, interviewed “over 50 people, including many Black Georgians immersed in the problems of race: voting-rights activists, politically engaged ministers, community leaders, civil-rights and defense attorneys, politicians, law enforcement officers and ordinary citizens.” I would not be surprised if many of them are directly quoted in the book’s dialogue. And ideologically, there’s not much here that Twitter could fault Patterson for. Trial mostly consists of Black characters lecturing the appropriately humble and attentive Chase on everything from insurance redlining and tokenism to voter suppression and the agonies that Black mothers feel about the safety of their sons. Their statements, and the novel’s manifest endorsement of them, are exactly on point according to current liberal/left thinking on these issues. Chase, a former prosecutor, joins as co-counsel, but the lion’s share of glory goes to the Black attorney Allie brings in to defend Malcolm, so Patterson steers clear of the dreaded accusation that he’s crafted a white savior narrative. If you believe that the role of a novel is to comprehensively instruct its readers on the correct moral position to adopt on political, social, and identity issues—and a lot of people do seem to take this view—then Trial is a nonpareil specimen of the novelist’s art.

Does this make Trial “authentic”? I’m not in a position to verify how accurately Patterson depicts Malcolm as he drives down a dark Georgia back road, with Killer Mike “rapping on his sound system, rapping an anthem to resisting the police.” But the novel’s Black characters do feel one-dimensional to me, noble sufferers and crusaders whose only flaws are the flashes of impatience they feel at the stubborn injustice of their lot—if that can even be called a flaw. Here’s the rub, though: Patterson’s white characters also strike me as flat. All of Patterson’s characters are flat. Unlike real people, they all say exactly what they think, feel, and mean in fully formed paragraphs. This comes with the territory in many popular thrillers, in which everyone is broken down into camps representing either Good or Evil, and characters possess, at most, one or two personality traits that fix them as specific types.

In Patterson’s defense, once Malcolm’s trial finally begins, the novel picks up, and the gambits and maneuvers of the lawyers and judge generate a good amount of suspense. But that doesn’t happen until two-thirds of the way through the book, and what comes before is a soap-operatic slog laden with tendentious speeches about American race relations. For a reader who’s thought with any depth about these issues, none of it will be anything you disagree with—but also, none of it will be anything you haven’t heard many times before.

Patterson aims to do something worthy here, to foster more empathy in white Americans for the toll that racism exacts from Black Americans. He’s clearly worked hard to understand as best he can what dealing with this feels like to Black people, which is more or less what racial justice activists are always urging white allies to do. Maybe some readers will find that these complex ideas still have dimension, even when delivered by cartoon characters. Maybe an extremely basic legal thriller by an established, bestselling white author is a good way to introduce structural racism to a white audience, if there’s one out there that hasn’t encountered the concept before. Maybe.

But none of that is enough to make Trial a good novel—by which I mean a novel I can ever imagine enjoying. This isn’t to say that Trial couldn’t sell. I find the characters in John Grisham’s novels boringly generic as well, and Grisham reliably moves millions of books. But it’s difficult for me to criticize book editors who, faced with a bland, preachy thriller by a once-famous author, turned it down, no matter how elevated its intentions. In his Wall Street Journal essay, Patterson assures us that many of the editors who rejected Trial told him that they found the novel “impressive” and “opined that it evoked my best work.” It was only his race, he says, that prevented them from accepting the manuscript. I wonder, though, if they might not have been passing the buck, as editors have been known to do. Perhaps it’s easier to blame the scolds of social media and the junior staff than it is to tell a onetime ace that he’s lost his fastball just as his comeback attempt has begun.