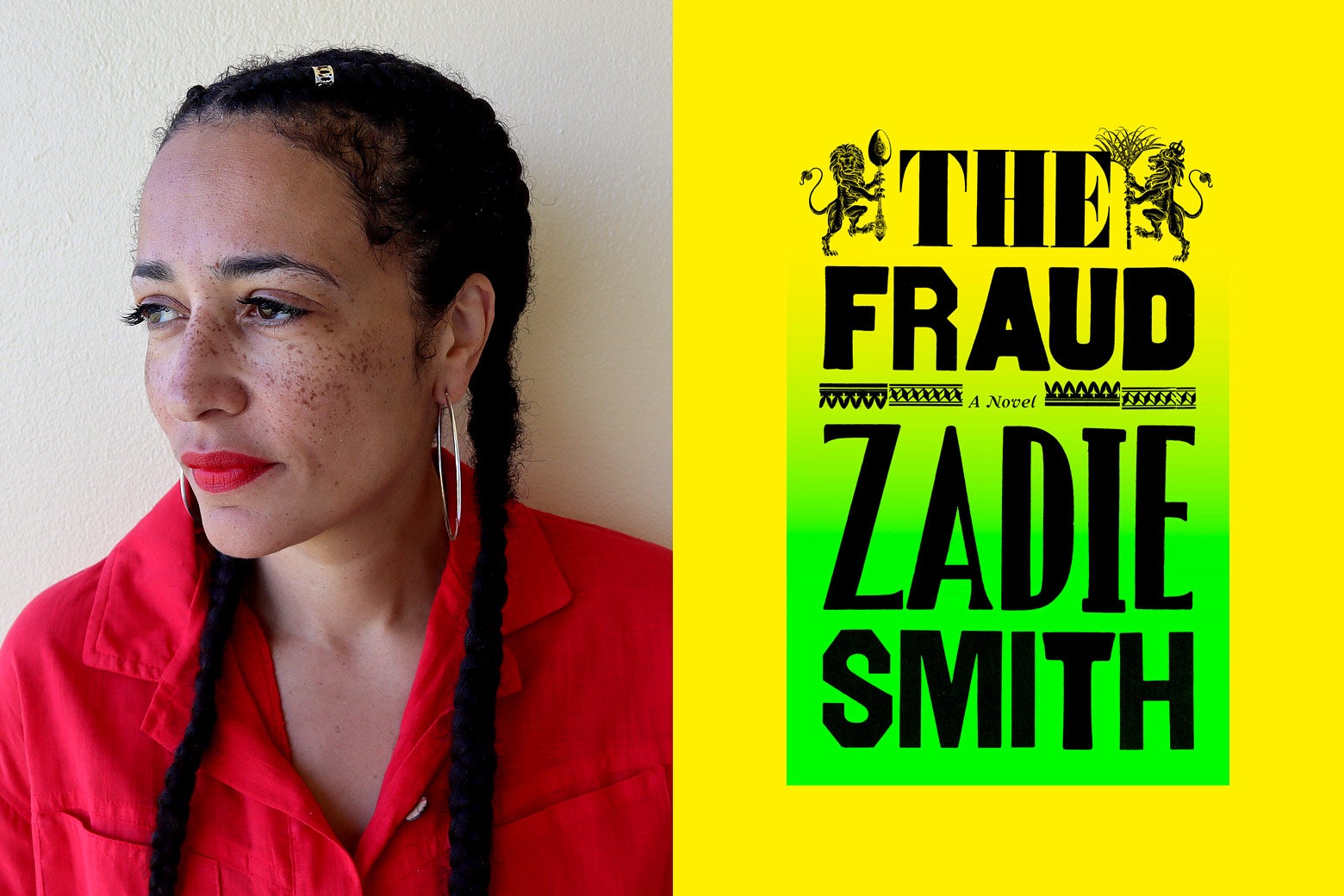

Gabfest Reads is a monthly series from the hosts of Slate’s Political Gabfest podcast. Recently, Emily Bazelon spoke with author Zadie Smith about what Charles Dickens got wrong about slavery—and why it doesn’t really matter—in her new novel The Fraud.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Emily Bazelon: I can’t resist asking you an actual historical question. You tell us that Charles Dickens, the real novelist, the famous novelist, was on the wrong side of the 19th century debate about Jamaica, about the rebellion of enslaved people in Jamaica. So, what are we to make of this? How do you think about Dickens when you include this fact about him in all the other things that we think about him and his great empathy for all his characters?

Zadie Smith: This is so far out of the logic of present life at the moment, but I don’t think you have to make anything of it. I mean, you can make what you like of it, but the idea that what we make of someone fundamentally affects them? Charles Dickens is dead.

So, whatever you make of him, it’s about yourself. You have the choice to make your feelings one way or another. For me, it’s just a fact. It’s an added fact to all the other facts about him. And it’s completely in line with that part of him which dreaded chaos. He dreaded fuss, chaos, violence. He didn’t really want to think about the Colonies, particularly apart from in their kind of most American fabulous version. But at the same time, when he went to America and went south and saw Southern American slavery, he was absolutely horrified and said he wouldn’t read in any of those states. So, he is a man of contradictions.

I don’t know why it isn’t possible to hold more than one idea in our heads at the same time. And I can hold in my head the idea that Dickens is an extraordinary writer and also was completely wrong on the Jamaica question.

Right. I mean, one thing I thought about is that, and there are lots of examples of this, but sometimes I feel like we want people from the past who we think of as beloved to be ahead of their time in their virtue. And that’s just not a reasonable test; they’re not going to pass.

But it’s so narcissistic as well. Why do you assume you are ahead in virtue? I find that idea absolutely narcissistic and inaccurate, to be honest. So, even the boundaries of the test don’t make sense to me.

And then so, just to help me square that, how does that idea of virtue being narcissistic square with how we would think back on this piece of Jamaican history today?

What I mean is that the idea that you are the most progressive people who the world has ever seen is narcissistic and incorrect. It is presently the case that the same people making these arguments are, for instance, in a common example often given, wearing clothes made by Uyghur Muslims who are in conditions of complete confinement. Or the phones that we use that we know have materials in them mined by children. You are constantly in a state of absolute moral peridot around other situations. That’s a situation we are all in all the time. So, the idea of feeling superior to the past or infinitely superior to the past, I find really peculiar.

That is a great lead into the last question I want to ask you, which goes back to the title of your book, The Fraud. Is everyone in the book a fraud?

Yes, but that’s OK. It’s OK. You can still come together in large political movements of solidarity and not be Jesus Christ himself. That is not necessary for political action. All that’s necessary for this selection is will, solidarity, and action. Not perfect humans. That is not what’s necessary.

And what’s the role of writers and storytellers here? I mean, are they frauds? Is it actually helpful?

Almost always. First of all, it’s not for any writer to tell the public in what ways they are helpful. That is another narcissistic delusion. But what I hope for—that you could say that, “what I hope for”—is, when I think about people who actually are serious political actors, who are actually performing grassroots actions, changing things, putting pressure on people out in the streets. Those people, who I admire very much—the only thing I think writers can offer them is a slightly more complicated version of the people. That’s it. So that when they’re out on the barricades talking about the Black man, the white man, the cisgendered, whatever they’re talking about, that instead of that flat, cartoon person, what writers can offer is a slightly more complex version of the people that they’re fighting for. Of the people themselves. That is as far as I have ever hoped anything I’ve written to go. And if it can be utilized in that way and used in that way, I’m always happy, but I assume nothing more.